|

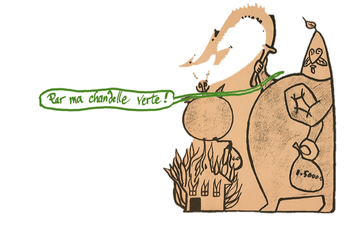

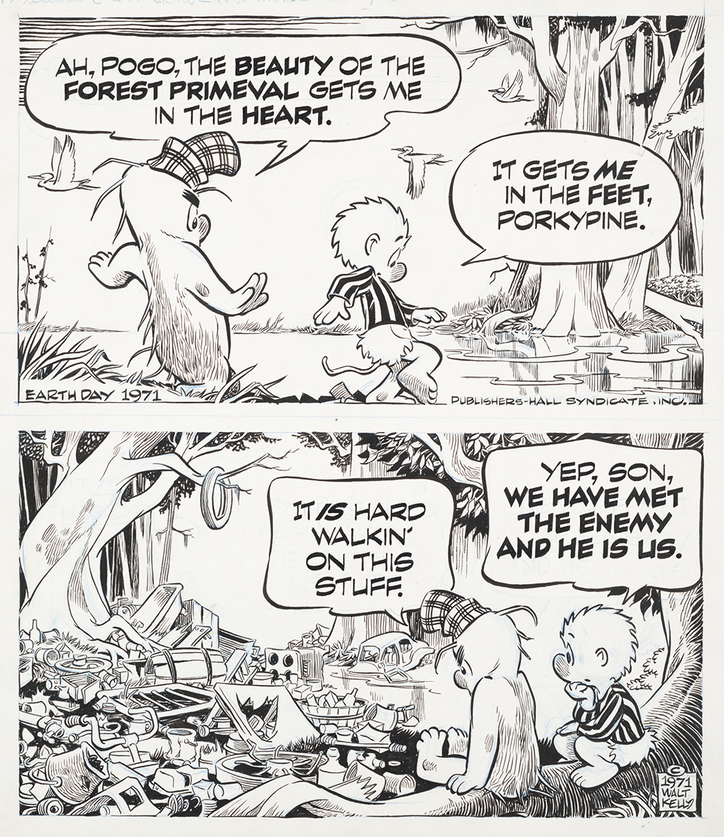

PASC is grateful to Okefenokee Glee & Perloo, Inc., for kind permission to reprint Walt Kelly’s "Pogo" daily comic panel of April 22, 1971, and the corresponding poster of 1970. Okefenokee Glee & Perloo may be contacted by emailing

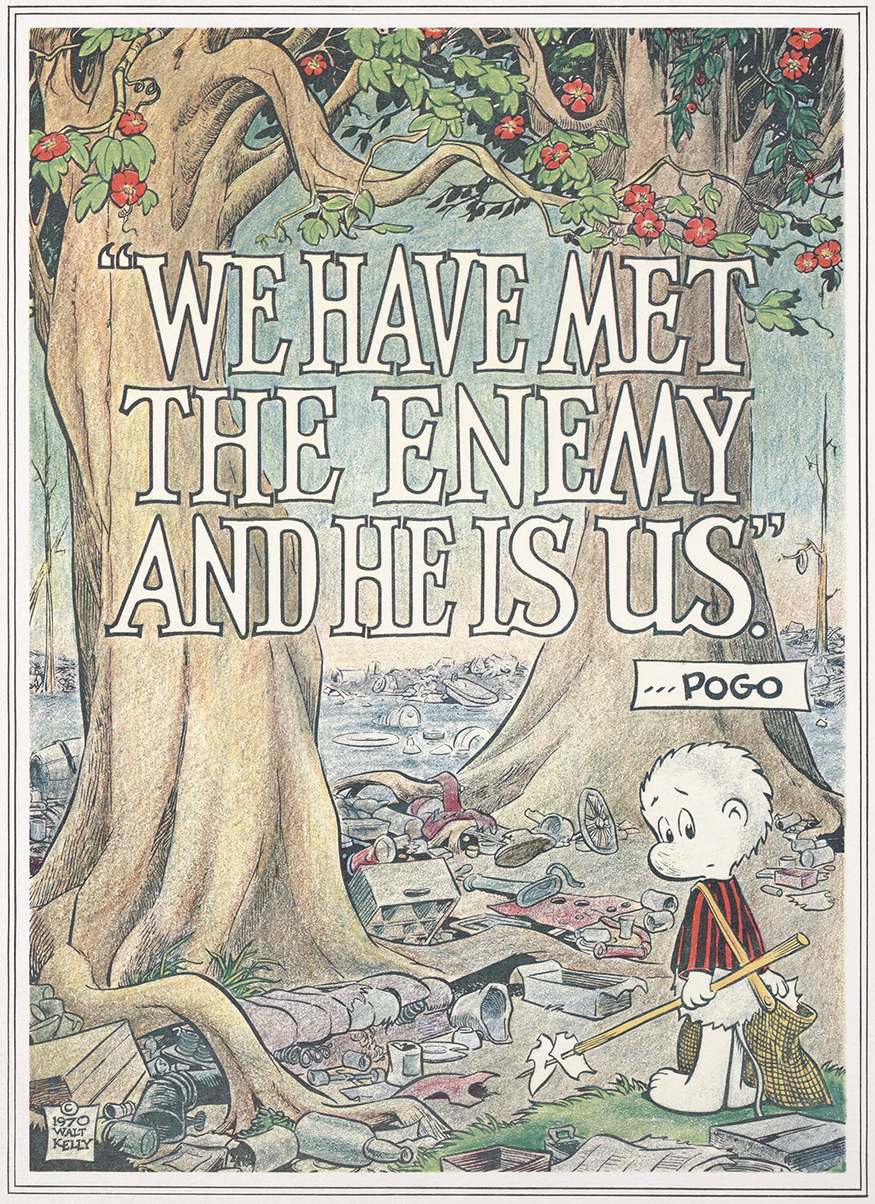

[email protected]. We thank the Earth Week 1970 Committee of Philadelphia for use of the Earth Week logo and all photographs (unless otherwise credited), which are © 1970 Earth Week Committee of Philadelphia and granted free use under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license. For history and links, visit EarthWeek1970.org. |

The Philadelphia Avant-Garde Studies Consortium (PASC) invites you to participate in its Symposium:

Avant-Green, Radical by Nature Environmentalism, Ecology, and the Natural World in Avant-Garde Art and Thought of the Anthropocene Fall 2024 The Philadelphia Avant-Garde Studies Consortium is seeking proposals for papers, lightning presentations, performances, and exhibitions for its Symposium, “Avant-Green, Radical by Nature: Environmentalism, Ecology, and the Natural World in Avant-Garde Art and Thought,” which will be held in the Spring of 2024, date TBD, a hybrid event in Philadelphia and online. All works/presentations will also be archived on our website.

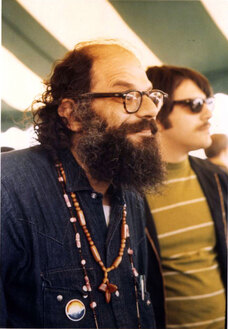

In many respects, the avant-garde has often “made it new” by returning to the oldest element of human experience: nature. Although artists and thinkers of all types have celebrated the beauty and sublimity of nature for millennia, it was not until the Industrial Revolution that they began to see it as endangered. Poets, novelists, and philosophers, from Emerson and Thoreau to Zola, Dickens, and Nietzsche, viewed nature as a source of life-affirming energy, but one that was under assault from a destructive, dehumanizing urban-industrial world. As the 19th century progressed, the natural world proved increasingly vulnerable to the forces of capitalism and consumerism, and by the mid-20th century, after the devastation of two world wars and the dropping of two atomic bombs, the thought that the entire planet could soon embody “The Waste Land” that T.S. Eliot had depicted in 1922 was not far-fetched. Although nuclear holocaust was averted (or at least has been so far), at mid-century the combined forces of Big Business and Big Science dominated US economic and technological policy and created an international capitalist juggernaut that cleared massive amounts of natural land, pumped enormous quantities of pollutants into the air and water, and created an increasingly artificial world and ailing global ecosystem. With it came increasingly dire revelations and warnings by artists and thinkers about the profound damage that military-industrial society was doing to the planet, whether in Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Alain Resnais’s film “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and “Wales Visitation,” Gary Snyder’s Earth House Hold, or Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi,” with its famous lyrics, “Don’t it always seem to go that you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone; they paved paradise, put up a parking lot.” |

|

Walt Kelly’s well-known "Pogo" daily comic panel of April 22, 1971, is © Okefenokee Glee & Perloo, Inc. Used by permission. Contact [email protected].

|

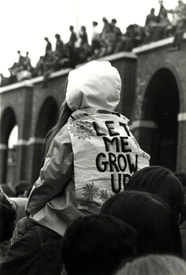

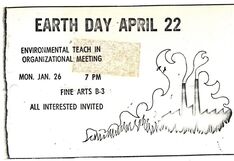

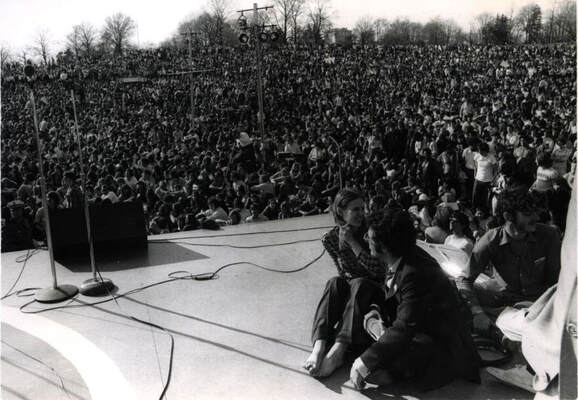

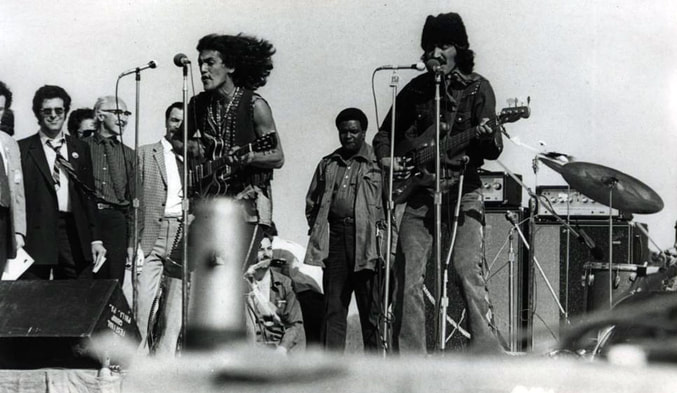

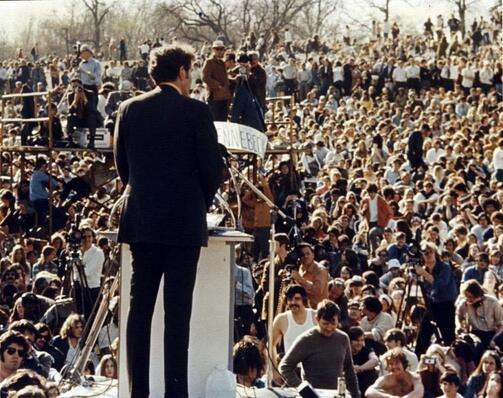

This green cri de coeur of the counterculture helped give birth to the first large-scale environmental movement in America. Less than one year after the Cuyahoga River in Ohio caught fire because it was so polluted, the first Earth Day took place on April 22, 1970, and eight months later the Environmental Protection Agency was established. Environmentalism, especially in the US in the 1960s and 1970s, had a dual identity as both “radical” and mainstream. Many dismissed it as the utopian pipe dream of Thoreau-reading hippies, yet the movement also marked the beginning of a significant sector of the government and the general population awakening to ecological reality.

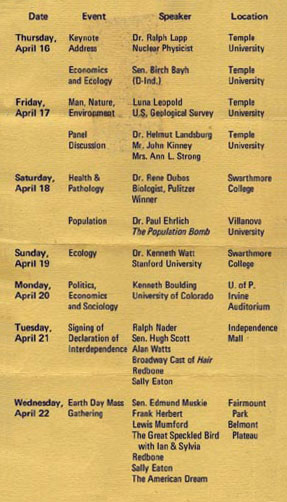

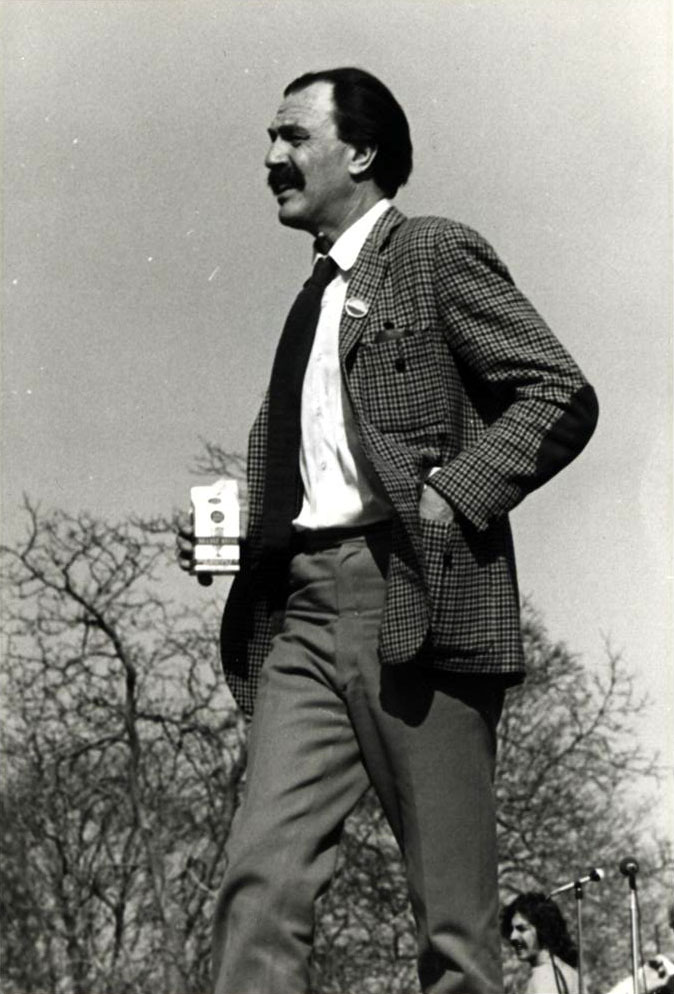

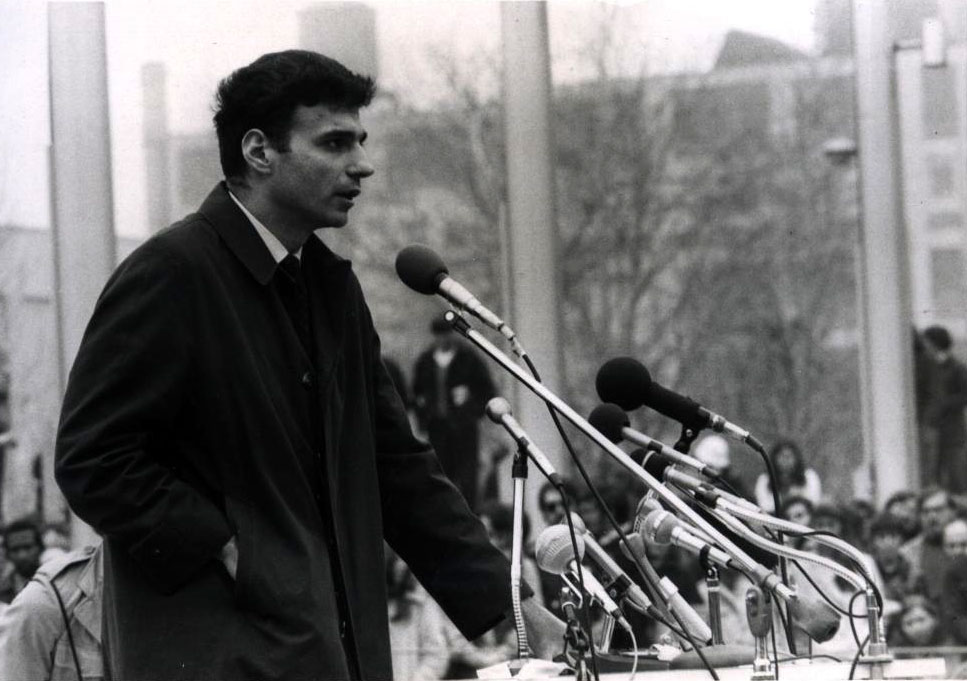

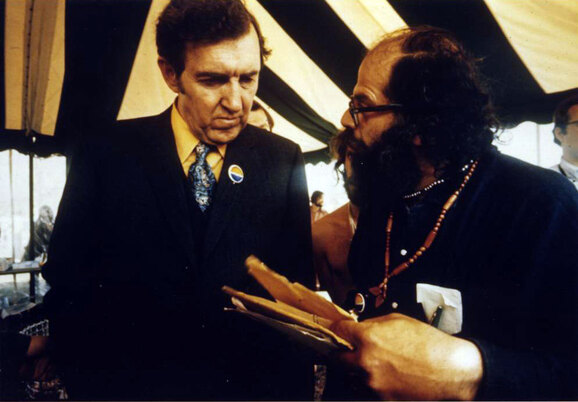

Philadelphia played a crucial role in this eco-awakening, and in the success of the first Earth Day in particular. In fact, Penn faculty and graduate students were the central organizers of Philadelphia’s Earth Day celebration/protest. Led by Penn Landscape Architecture and Regional planning professor Ian McHarg, whose book Design with Nature had just been published, Penn grad students and faculty were able to bring together a diverse coalition and stage a very large, high-impact event. As Walter Cronkite reported on CBS, “One of the biggest Earth Day observances was in Philadelphia…. It was an Earth Day success story, a major demonstration in a major city.” Just as significant as its size was the fact that Philadelphia’s Earth Day spanned the political spectrum. Counterculture icons Ginsberg and Ralph Nader spoke to the crowds gathered in Fairmount Park and at Independence Hall, but the demonstration was also funded in part by Philadelphia Gas Works and the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce, among other traditionally “square” organizations, showing that the environment was an issue that could generate significant political consensus. Philadelphia’s Schuylkill Center, founded in 1965 and “one of the first urban environmental education centers in the country,” was also part of that crucial early-stage environmentalism that helped plant the first seeds of change not only for Philadelphia but the nation and the world. |

Is

|

Although the early environmental movement raised awareness and considerable progress was made on some problems as a result of it, unfortunately, overall global environmental health has worsened dramatically since 1970. From the first Earth Day to the present day, there has been a growing list of unprecedented environmental crises, creating the convergence of interlinked problems, including global climate change, deforestation, nuclear disasters (Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, Fukushima); oil spills, mass extinction, habitat destruction, biodiversity loss, microplastic pollution, ocean acidification, droughts, floods, wildfires, and killer heat waves, to name just a few.

During the last 40 to 50 years, these escalating crises have elicited a wide range of artistic responses, from the techno-dystopia of David Lynch’s Eraserhead, to Thomas Pynchon’s eco-novels such as Vineland and Mason & Dixon, Agnes Denes’s “Wheatfield—A Confrontation” (1982), Natalie Jeremijenko’s “Tree Logic,” Richard Powers’s 2019 Pulitzer-winning novel about trees, The Overstory; Cai Guo-Qiang’s “Ninth Wave” exhibition addressing water pollution in China, Olafur Eliasson’s body of work on climate change, such as “Ice Watch” (2014) and, more locally, the Schuylkill Center’s Environment Arts Program, which, since 2000, has explored the pressing environmental problems of cities and fostered the work of dozens of artists to “engage with the environmental issues of our time.” All of these works, individuals, and organizations grapple with various aspects of the technoscientific, capitalist-consumerist society that created an over-arching environmental crisis of previously unimaginable urgency: We are now rapidly moving toward making our own planet uninhabitable. Yet, at the same time, there is reason for hope. Because of the great progress in wind and solar energy, electric cars, green building, and other sustainable technologies, we as a global society can reverse this trend if we can motivate citizens and politicians to take serious action now. At this unique eco-historical tipping point, the arts have a greater role than ever before in raising awareness and changing minds to spark political change on what is arguably not only the most important issue of our time but quite possibly of all time. We are seeking presentations from individuals, groups, and collaborating artists and/or scholars in four major categories: scholarly papers (max 20 minutes); lightning presentations on artistic and scholarly projects (max 7 minutes), small-scale exhibitions, and brief performances (max 10 minutes). In examining your avant-garde figure, group, theory, or movement (roughly 1875 to the present; local, national, or global), you might consider one or more of the following questions:

An updated Call for Papers will be published in Summer 2024. |

What

|

Thank you.

Walt Kelly’s "Pogo" poster created for the first Earth Day in 1970. © Okefenokee Glee & Perloo, Inc. Used by permission. Contact [email protected].