Jim Brewton, Graffiti Pataphysician

BY EMILY BREWTON SCHILLING | April 24, 2015

What a joy to participate in PASC ...

|

... and celebrate Philadelphia’s artistic vanguard! Through PASC, the James E. Brewton Foundation is offering opportunities for research, cataloguing, and detailed studies related to Jim Brewton’s life and work. I recently donated much of the Brewton ephemera to the University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Most of the artwork is stabilized and awaits cataloguing, assessment and conservation. There is still some detective work to be done—I’d estimate there are about 30 more pictures out there—and the artworks and ephemera offer many tangents to explore and connections to make. If you think you’d like to get involved, we’d be delighted.

In this blog entry, I’d like to present some background about Jim and how his art relates to important avant-garde movements in Philadelphia, the United States, and Europe. Then I’ll introduce one of his collectors, Bruce Broede, as a sample of my initial research efforts. First, a little bit about the Brewton Foundation and the work we’ve done so far. The James E. Brewton Foundation is a Pennsylvania-based 501(c)(3) nonprofit. We have two basic goals. First: find, conserve, and catalog the art. Second: work with educational and cultural institutions to preserve the work, and offer access to scholars and to curators for research and the works’ exhibition. |

|

Jim was my father, an avant-garde painter and printmaker who died by his own hand in 1967. Our household in Philadelphia had very few of his pictures (my parents had broken up), and I grew up knowing little about his art. After two memorial shows in Philadelphia—in 1968 and 1971—his artwork was dispersed and the world forgot Jim. Thirty-seven years passed. On a February afternoon in 2008, I noticed an ad in an old copy of ARTNews. It was for Michael Taylor’s show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, “Thomas Chimes: A Life in Pataphysics.”

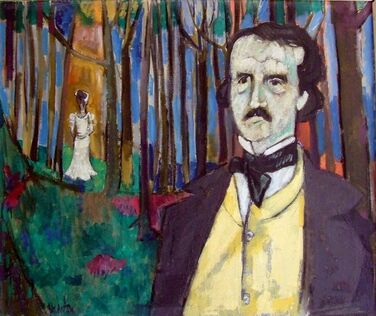

“Pataphysics” got my attention; I vaguely remembered Jim’s print, The Pataphysics Times (1964). I’d thought Jim was the only Philadelphia artist who admired Alfred Jarry, back in the day. I sent a letter to Michael and was bowled over when he called me. He was interested in Jim’s work, and he encouraged me to start searching for individual pieces, “sooner rather than later.” The memories were painful, but I found more than a hundred astonishing artworks. The largest two troves were held by women named Patricia, a pataphysical non-coincidence that Jim would have enjoyed. I found many of his belongings, including art-making tools, sketchbooks, and notebooks. In 2012 we showed one of Jim’s pictures, a portrait of Edgar Allan Poe, at the Woodmere Museum in Chestnut Hill. In 2014, thanks to Michael Taylor and the organizers of Philadelphia à la Pataphysique, we showed nearly thirty works at Slought, taking the opportunity to have them cleaned and restored. Michael Taylor gave a talk about Jim. The audio is on the Slought website. |

|

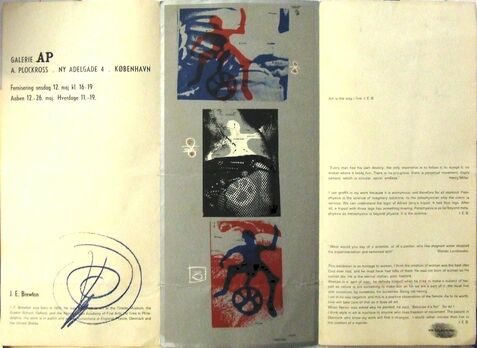

Jim was born in Ohio in 1930. After serving in the Marines in Korea, he went to art school on the G.I. Bill. He enrolled at the Ruskin School at Oxford, but soon transferred to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. His mentors at the Academy were Franklin Watkins, Hobson Pittman, and Ted Siegl. Jim’s work won awards and prizes, and he was championed by critics while he was still a student.

“Mr. Brewton’s career was launched dramatically,” ran his obituary in The Philadelphia Inquirer in 1967, “when his canvas The Suicide of Judas won the prestigious $1000 Scheidt prize …. [He] thus captured—at the very early age of 28—the same award William Glackens, Stuart Davis, Hans Hoffman, Ivan Albright and Charles Burchfield had earned in their maturity.” Considering Jim’s very traditional choices of Ruskin and the Academy, it’s intriguing that the primary influences on his work and life were André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Alfred Jarry and Asger Jorn. |

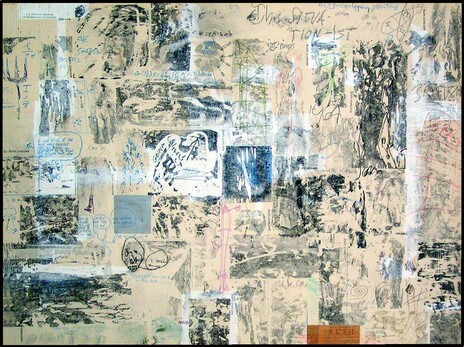

While at the Academy, Jim’s student job was at The Print Club (now Print Center), where he was electrified by the CoBrA artists’ work. Knowing how excited he was about CoBrA, Jim’s friend Claire Van Vliet introduced him to her friend Erik Nyholm, a close friend of Jorn. In 1962-63, and again in 1965, Jim spent time in Denmark with the Nyholms and Jorn. Back in Philadelphia, he continued to innovate, synergizing the concepts he admired with his own lyrical style. He called his method “Graffiti Pataphysic.”

In May 1967 Jim and Fluxus artist Jim McWilliams (also a friend of Claire’s) organized a pataphysics-inspired show at Perakis Gallery, but three days before the opening, Jim shot himself. During the years that followed, his works were scattered. I knew of fewer than twenty in 2008.

In May 1967 Jim and Fluxus artist Jim McWilliams (also a friend of Claire’s) organized a pataphysics-inspired show at Perakis Gallery, but three days before the opening, Jim shot himself. During the years that followed, his works were scattered. I knew of fewer than twenty in 2008.

Discovering the Broede collection

According to an old exhibition catalogue, Bruce and Carol Broede had lent some exciting-sounding pieces to a show, including Ubu’s Military Mind, X and An Egg Carton for the Wall. When I searched for the Broedes in 2009, I learned they’d moved from Philadelphia to the Los Angeles area and had a son, Jason. In memory of their friend, they gave Jason the middle name of Brewton. Since then, they had divorced, and Carol remarried. She has been extremely helpful and generous with her time.

“I do remember X,” she told me. “I believe the portion on the bottom was made from a cardboard type of box, similar to the egg carton, that had held forks, or some other silverware. It was truly a show-stopper." Carol helped me get in touch with Bruce. He’d had major surgery, but he talked with me a few times. Below are his recollections:

“I do remember X,” she told me. “I believe the portion on the bottom was made from a cardboard type of box, similar to the egg carton, that had held forks, or some other silverware. It was truly a show-stopper." Carol helped me get in touch with Bruce. He’d had major surgery, but he talked with me a few times. Below are his recollections:

“Jim worked for me at the University of Pennsylvania book store," Bruce remembered. "The reason I got The Pataphysics Times was, I was able to order a display of paints, dozens of different tubes of paint. They were delivered to the store for display, and I gave them straight to Jim to take home. In return, he gave me a copy of The Pataphysics Times.

“I bought Last Game and No Birds in the Sky in the last year before his death," Bruce said. "Last Game: metal stuff was used as paint on the canvas, and then he rolled balls onto it. He left them where they fell—fifteen balls for the game of pool. The white X was the cue ball. The shadow of the pool player was from a famous photo of a shadow burned into a bridge [by a body] at Hiroshima.

“No Birds in the Sky was a metal sculpture with a Styrofoam bird up in it," Bruce continued, "gigantic, disguised as an airplane, dropping a bomb. Jim was fixated on Hiroshima. In 1990 I was going to live with my sister in Bismarck and had the two big paintings sent there. They were still in the shipping crates when I left. Now we’ve cut off all contact.

“I bought Last Game and No Birds in the Sky in the last year before his death," Bruce said. "Last Game: metal stuff was used as paint on the canvas, and then he rolled balls onto it. He left them where they fell—fifteen balls for the game of pool. The white X was the cue ball. The shadow of the pool player was from a famous photo of a shadow burned into a bridge [by a body] at Hiroshima.

“No Birds in the Sky was a metal sculpture with a Styrofoam bird up in it," Bruce continued, "gigantic, disguised as an airplane, dropping a bomb. Jim was fixated on Hiroshima. In 1990 I was going to live with my sister in Bismarck and had the two big paintings sent there. They were still in the shipping crates when I left. Now we’ve cut off all contact.

|

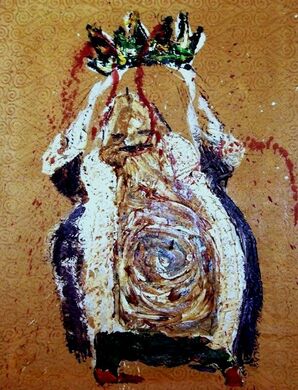

“Ubu’s Military Mind is really heavy," Bruce said. "He had his signed military medal from Korea on the front and some numbers on it as well. The figure of Ubu is defecating – Jim’s medal is the turd.”

“I remember … Bruce and Jim laughing about it,” said Carol Broede Olson. |

'He was so far ahead of his time'

|

"[Jim] was very dedicated," Bruce Broede told me. "He had a disc problem in his back and every once in a while he’d be in the hospital in traction. He was very depressed that the disc in his back was worse and worse. He would not physically be able [to paint. I went to see him] in hospital again…. He was figuring out how to get a canvas on the ceiling and long paint brushes so he could paint that way.

“He was so far ahead of his time. He was working on a triptych when he died—it was made of wood and had two sides attached with hinges; it opens at the sides. It was about Admiral Nelson, but he hadn’t finished it.” |

Emily searched for the two lost paintings ...

|

I tried to find the two big antiwar paintings left in Bismarck, N.D. Bruce’s nephew, Steve Berg, recalled: “I remember that painting well. It was huge, it was in the garage, and it had balls on it. They were falling off because it didn’t have the care that it should. I remember really looking at it; it was abstract, and you had to study it to appreciate it. The colors. But I’m afraid those paintings are gone.”

In August 2009, I received a packet of photos from Bruce, showing his collection. When I called to thank him, I got no answer. The following month, Carol emailed to say that Bruce had died. His paintings now belong to his son. In December 2010, my husband and I went to Sierra Madre to meet Carol, her husband Eric Olson, and Jason. I showed them my Brewton catalogue. Jason zeroed in on No Birds, coming to an image I’d plucked from WHYY film footage of the 1968 memorial show. He agreed with his cousin that the paintings were almost certainly lost from his aunt’s house in North Dakota. After lunch, we looked at the Broede collection. |

|

Ubu’s Military Mind was taller and narrower than I’d thought, and quite heavy, as Bruce had told me. X was more fragile than I’d believed, but every bit as magic. It looked like a frieze from an ancient tomb, conjuring a rite of supplication to the sun. Yet it was made with silverware packaging.

An Egg Carton for the Wall carries much more gravitas than I’d expected. The Brewton Foundation is looking for ways to help preserve the works in the Broede collection. After the show closed at Slought, Jason allowed us to store Ubu’s Military Mind with the main Brewton collection in Philadelphia. It awaits conservation there. |

From the Brewton Foundation

From the Brewton Foundation’s board of directors, and from me personally, we are delighted to offer Jim’s work and ephemera for study through PASC. If you’d like to participate, please email [email protected].

I am profoundly grateful to Michael Taylor, who set the Brewton project in motion. For their enormous kindness, I wish to thank John Heon, Aaron Levy, David McKnight, Katie Price and Jean-Michel Rabaté. For more images of artwork and information about Jim, please visit www.jebrewton.org.

I am profoundly grateful to Michael Taylor, who set the Brewton project in motion. For their enormous kindness, I wish to thank John Heon, Aaron Levy, David McKnight, Katie Price and Jean-Michel Rabaté. For more images of artwork and information about Jim, please visit www.jebrewton.org.